Our Philosophy

Most photography schools offer the same product.

In attending one you can expect the instructor to take you through all of the various features and settings on your camera, impart some standard advice on how to compose an image, before eventually discussing how to shoot some tried-and-true industry formulas such as headshots or food photography, etc.

The only thing that ever really changes is the hook…. the school’s unique “branding.”

For instance, some programs try to separate themselves by appealing to one unique personality type, like “adventure travelers” as opposed to “fine artists.” Others schools do so by hiring a notable ‘big name’ photographer to be their instructor. And still others by curating a unique, destination experience at some exotic location.

But underneath all of that, when it comes to the actual material they’re teaching, these programs offer the same basic shooting strategies, and impart the same kinds of ‘common wisdom,’ that can be found in countless online tutorials and YouTube videos.

But at ASOP, we aren’t teaching the same material that everyone else is teaching, but under a different brand……we’re teaching entirely different material altogether.

And we’ve worked hard to ensure that our course material is far more sophisticated and comprehensive than what’s offered in other workshops and tutorials, while still being totally engaging and accessible to the layperson.

So how can we do that?

Well, our program benefits greatly from the fact that we aren’t working within any one established segment of what you might call “photography culture.” And similarly, we make it our aim to ensure that we aren’t working exclusively with aspiring professional photographers.

Wait, so why is that a virtue?

Because dedicated photographers make up only a small fraction of the people out there who can really benefit from having advanced photographic skills. And more to the point, we’ve found that a lot of photography programs have become fairly limited — bogged down even — by their continued adherence to some pretty lazy industry trends and jargon (trends and jargon that have been very carefully marketed toward “photographer culture”).

And to our mind this has lead to a stifling of photography’s potential, blocking this medium’s advancement into becoming a more complex and more adaptable form of visual expression.

So while our program continues to train professional photographers - and train them well - professional photographers account for only about 30% of our student base.

The other 70% of our students are people who are just curious to learn. They’re chefs, architects, psychologists, marketing consultants, stay-at-home-parents, retired military personnel, software engineers…you name it. And working closely with this rich mixture of students these past 10 years has contributed entirely different kinds of knowledge and experience to our curriculum.

For instance, many of the engineers who’ve taken our classes have contributed insights into how the science of photography works beyond the limited abstractions that have been presented to people on their camera’s interface. And this in turn has ensured that future ASOP students will better understand what is actually happening beneath the surface of their technology, as opposed to just memorizing the patterns and reference points that’ve been engineered into their camera’s operating system.

On the other end of the spectrum, psychologists who’ve taken our classes have contributed insights into how people are likely to “read” an image, or perceive an image.

Marketing experts have contributed insights into what makes an image more persuasive to the public, or how people are likely to respond to an image.

Artists and other creative professionals have provided insights into the ways that photography can overlaps with - or supplement - other forms of visual media, such as painting, graphic design, or cinematography.

Software developers have provided insights into what the programmers at Canon/Nikon/Sony were thinking when they designed your interface.

We’ve had fashion designers take these classes, independent filmmakers, watercolor painting instructors, extreme sports enthusiasts, people who’ve designed optical devices for medical companies, New York Times journalists, ballet dancers….Etc. Etc. Etc. And each of these remarkable people has contributed something to our curriculum, whether it be about science, or about art, or about communication, or about the dynamics of human movement.

So whereas most mainstream photography wisdom stems from the photography community’s somewhat superficial, “jack-of-all-trades” understanding of each of these disciplines (as well as the broad tendency to trust in the “solutions” engineered by Nikon, Sony, and Canon)…..ASOP’s curriculum stems from collecting more specialized, concentrated expertise in each of these areas.

In doing so, this curriculum has evolved and detached from mainstream photographic thinking almost entirely, and we’ve begun to embrace our own totally unique approach.

We’ve found this approach to be far more accurate and more effective than what we were originally taught, and moreover, we’ve found this approach to be more inclusive of a wider range of personality types.

And we’re very proud to say that our program’s effectiveness is now tangibly represented in the work that our students produce, as well as in the diversity of students who produce that work.

In short, ASOP has inadvertently become something of a photography think-tank. And whether you’re a stay-at-home parent wanting to foster a deeper sentimentality in the pictures you take of your children…..or you’re an engineer who’s fascinated by all different kinds of applied sciences…..or you’re an artist looking to mold the world around you into a more concise expression of your own unique vision….our program has evolved to accommodate each and every one of those very disparate interests.

In exchange, this rich mixture of students contributes valuable insights that often go undetected by programs more entrenched within established photography culture, or programs more geared toward one specific demographic.

An In-Depth Look at How our Program Works

So what makes ASOP different?

To understand how our program works, let’s examine 4 very common assumptions that often lead photographers to limited and compromised results, and then we’ll illustrate how our program approaches each of those assumptions very differently.

Assumption #1

Photography is all about subject matter. If your photograph is good, it’s because you had a good subject.

Photographers put a lot of stock in their subject matter. That probably goes without saying.

In fact, photography might be the only creative act for which people routinely mistake the mere choice of subject matter for being the actual medium itself.

What do we mean by that?

Well, if you were to ask other kinds of artists to define themselves, most of them would do so in terms of style, not content.

For instance, ask someone “what kind of musician are you?” and they are likely to answer that they are a jazz musician, or a classical musician, rather than responding with a very specific song topic.

Likewise, “impressionist” painters and “surrealist” painters often paint the very same subjects (a bowl of fruit, or the Eiffel Tower, for instance), and yet their paintings exhibit such different traits, and appeal to such different people, that we put those painters in entirely different categories even when they ARE painting the same subject.

So other artists are defined and categorized by the style or manner in which they use their medium, and not by the specific subject they happen to be addressing at any given moment. We acknowledge that there is both the content that they have chosen, and also the way they have used their medium in order to address that content. And it is more in the latter, in the addressing of the content, that their identity is understood.

But this isn’t the case for photographers at all.

Photographers define themselves almost exclusively by the content they shoot, and rarely by the way that they shoot it. In fact, if someone asks "What kind of photographer are you?” what they’re actually asking is ”what subject matter do you shoot?”

Are you a nature photographer? A sports photographer? A portrait photographer?

And to illustrate why this is such a problematic framework, let’s suppose that your answer to that question is that you shoot “sports.”

Ok, but do you shoot sports the way a newspaper photographer does, with a mind toward identifying a specific athlete?:

Or do you prefer to shoot sports as though they were a surreal and sentimental dream:

Or maybe you want to create visual abstractions using the movements of athletes:

Or maybe you want to portray sports as introspective moments of intense concentration and discipline:

Note: all of the above photographs, with the exception of the “newspaper” images, were shot by ASOP students

That so many photographers define themselves by the subject matter they shoot is problematic, because, on the one hand, it’s a really vague and imprecise way to define oneself, and on the other hand, it severely limits their development.

How so?

Well, when photographers are first starting out, they often frame their educational goals in terms of the specific subject matter they want to shoot. For instance, they’ll ask, “What lens should I use if I want to shoot landscapes?” Or “What camera is best for shooting architecture?”

And while such questions undoubtedly come from a well-meaning place, those questions really miss the mark. First of all, there are at least 3 or 4 types of lenses being used in the sports photographs above, so in order to answer the question “what lens is best for shooting sports?” we would first have to know how you want to portray the sports you intend to shoot.

Most likely the student asking that question is wanting to be taught the “conventional” method for shooting sports, which is probably something like the newspaper-style snapshots displayed above.

But one of the reasons this medium is evolving at such a painfully glacial pace is because most of our industry “expertise” revolves around photographers learning how to mimic and regurgitate the single, most established methodology for shooting a specific kind of subject matter.

And then the problem is, if photographers learn their skills through that kind of mimicry, most of them don’t really know how to break those processes down into their logical components so that they can then build them back up into something more sophisticated….or more unique, or more clever.

Which causes the photography industry to stagnate, often using the same basic formulas for decades on end.

But next, even once a student has moved past their initial incentive for wanting to learn photography, this fixation on subject matter is still a bit of a menace, because it frequently causes them to skip crucial developmental exercises, complaining that they couldn’t find “a good enough subject,” or anything “interesting enough” to shoot.

In other words, they’re showing up to class empty-handed, and having missed out on some crucial developmental experience, all because they couldn’t find a subject that they “liked” enough….when the skills we were addressing could have been mastered shooting any subject at all.

It’s as though they don’t feel like they’re allowed to pull out their camera unless they’ve first found a subject interesting enough to justify having pulled out their camera.

So all of this is to say that the very notion of “subject matter” really tends to stand in the way of student development.

And that’s why our program makes it clear from the start: it isn't so much WHAT you shoot as it is HOW you shoot it.

When a photographer encounters any subject at all, there are dozens of ways the medium of photography can be used to address that subject. Higher level photography is not about merely “capturing” something….it’s about using the medium to narrate, describe, or comment upon that something.

And while the above images are meant to illustrate several different approaches to sports photography in particular, I think the more fundamental idea we’re after will become clearer with this next demonstration.

The following images are pulled from an exercise we do at ASOP (meaning these images were shot by students less than halfway through our program). The goal of this particular exercise is to control the subject, while varying the STRUCTURE of the image:

In this first comparison, the image on the left depicts a cheap, miniature flag from the impulse aisle at the supermarket, whereas the image on the right is an archetypal depiction of “Old Glory” guiding us through dark times.

But it’s the exact same flag, just shot with two different technical strategies (and this effect was achieved in-camera, by the way, and not with post-processing).

In this second comparison, the image on the left does little to guide the viewer (ie: there’s no specific emphasis), which leaves the viewer to act on their own inclinations as to how their eyes should scan or “read” the scene.

Whereas the image on the right creates a clear foreground/background relationship - a layered hierarchy of information - which guides the viewer’s eyes more deliberately from foreground into background.

And in this last comparison, the image on the left depicts a very static car that’s parked in a parking lot, while the image on the right depicts a high speed, dynamic action sequence. But the scene and subject were identical, which is to say that the car is not moving in either picture (and once again, this was not done with post-processing)

So each of these pairs of images actually contains the very same subject, we’ve merely altered the way we’ve STRUCTURED the photograph.

And hopefully this demonstrates why choosing a subject is not the be-all-end-all decision when it comes to making a photograph.

Choosing a subject is merely the first decision.

But then, by changing the structure of the image, we can change the way the photograph describes or articulates that subject. And more importantly, we can get the viewer to perceive or digest that subject in one particular way, as opposed to another.

The phrase we often repeat around the ASOP studio is: the photograph is not a host for your subject matter. Rather, it’s the other way around. The subject plays host to whatever idea you want to communicate.

And you can impose any idea you want onto that subject. That is, you can “describe” or depict that subject in any way that you want.

But most photographers are looking at this the wrong way around. They’re spending most of their time looking for a compelling subject - or a good “moment” - and almost no time at all developing their actual photography skills (problematically, this is true even at the college and grad school levels).

Moreover, we find that once our students reverse their perspective on this, their ability to get what they want out of an image improves quickly and dramatically.

But having said that, we should also clarify that, yes, your choice of subject is still an important decision (of course it is), it’s just that when learning photography, subject matter isn’t the best place to start.

If you really want to master this medium, you first have to learn how to STRUCTURE your images. And then once you become more versatile and more adept at doing so, you’re free to seek out whatever subject matter you want and you’ll be amazed at how many ways you know how to articulate and express those subjects.

However, the frustrating reality is that most workshops and tutorials extol the exact opposite value; they actually lead with subject matter, before offering one or two formulaic methods for shooting it (ex: “how to shoot headshots,” or “how to shoot food photography”).

And this results in some extremely superficial photographic knowledge. Which is then regurgitated and repeated endlessly by our so-called industry “experts.”

But at ASOP, we have very little interest in producing students who simply memorize how to mimic a particular formula we’ve shown to them. Our job is to give students a fluent and adaptive set of abilities that will enable them to shoot any subject they want, and in ways that reflect their own sensibilities and preferences, and not the sensibilities of their instructors. Because, all too often, when students do attend a workshop on, say, “food photography,” they all leave that workshop shooting exactly the same way.

For us, the most rewarding aspect of this whole endeavor has been watching our students shoot sophisticated images that diverge both from what we shoot as instructors, as well as from what other serious photographers shoot.

In short, we want our students to be able to shoot any way that they want.

Assumption #2

Composition is everything. Once you’ve chosen a subject, the most important decision is how you frame, or compose the image.

As was the case with choosing the “right subject,” the virtue of choosing the “right composition” seems so self-evident that most photographers hardly question it.

But at ASOP, we need our students to understand that the term “composition” refers to a lot more than just how you’ve framed your image.

So what do we mean by that?

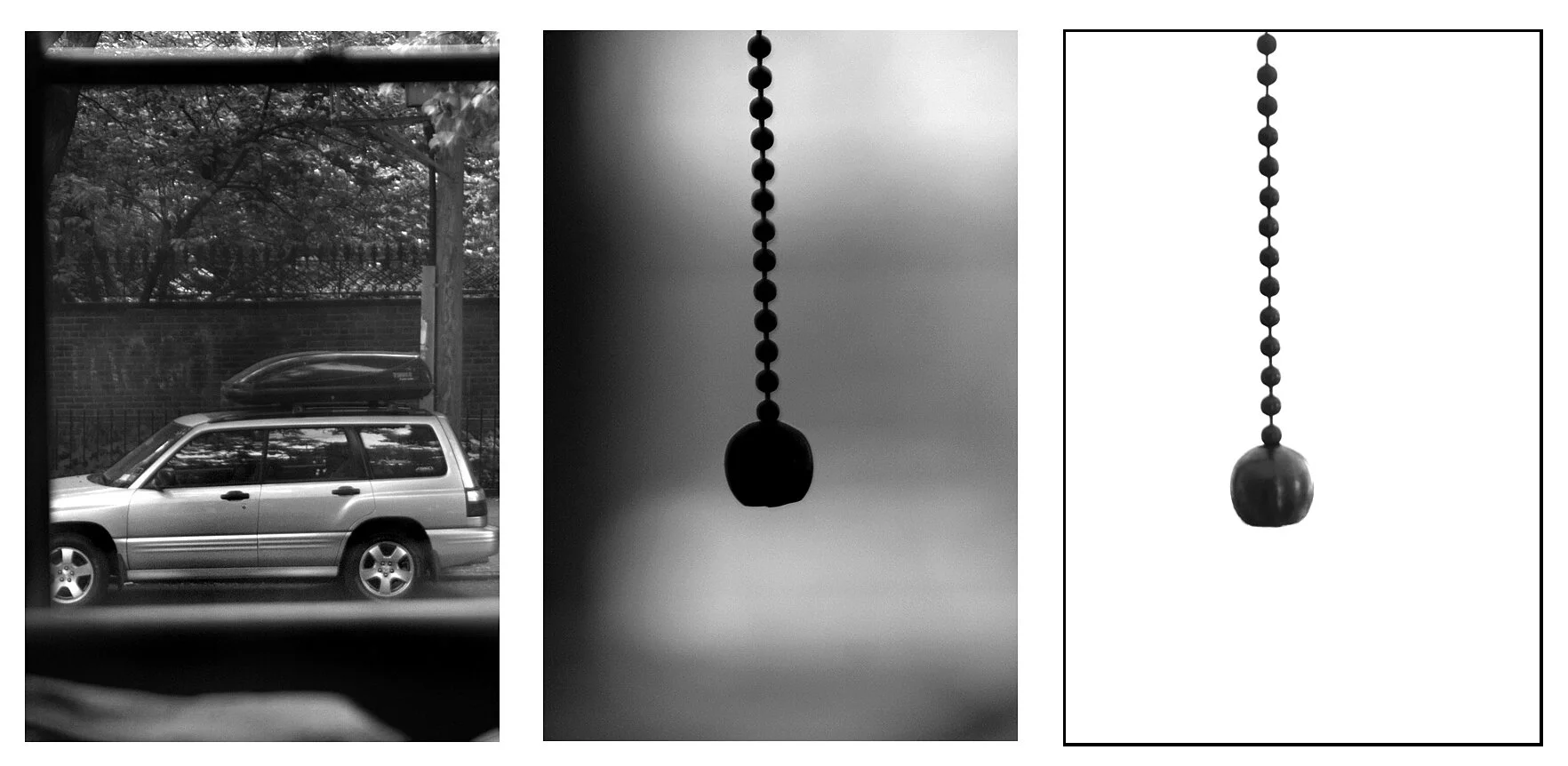

Well, consider the following comparison. Believe it or not, both of these images were shot using the same framing, meaning that they were taken of the same scene, with the camera in the exact same position:

Once again, these examples have been pulled from student exercises.

How is that possible? Well to understand what has been done here, let’s add one more image to the sequence in order to bridge the gap:

What we’re looking at here is a lamp chain hanging in front of a window. The vehicle is outside and much farther away, whereas the lamp chain is inside and very near to us.

As you can see, going from left to right, we’ve first swapped the focus from the background to the foreground. And then for the final shot, we’ve swapped the exposure (ie: we’ve adjusted the amount of light we’re capturing and made the image brighter).

Or to put it in more practical terms, for the first image, BOTH our focus and our exposure are set for the exterior of the scene (the background), and then in the final image, both our focus and our exposure are set for the interior of the scene (the nearground).

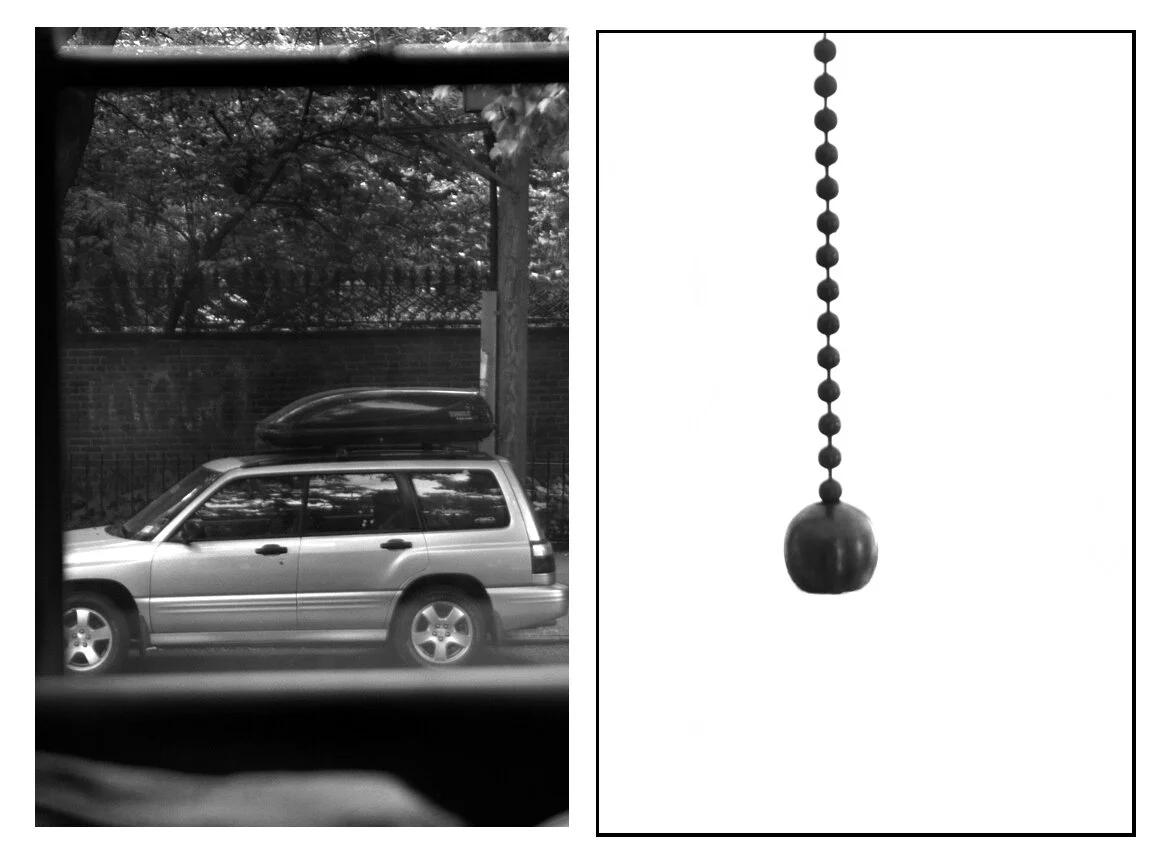

So if that illustrates how we got from one image to the next, let’s go back and compare those first two shots again:

As you can see, these two photographs have nothing in common. But they’re framed identically.

And we should clarify here that these two images are not meant to be ‘good,’ or even interesting images. This is merely an exercise we do with our students in order to demonstrate how much an image can be altered after you’ve already chosen your framing.

But then once you begin more deeply exploring these kinds of technical alterations, it becomes very apparent that just one single manipulation can change an image substantially. However, two manipulations can change an image entirely, which underscores the importance of ‘structure’ on even the AESTHETIC value of an image.

So just for good measure, here’s the exact same progression of shots one more time, but now done in reverse. This time we’ll start by darkening the exposure of the image so that the leaves become silhouetted, and then we’ll finish by swapping the focus from foreground to background:.

And once again, let’s cut out the middle shot and compare the two ends:

Again, these images have nothing in common.

But again, these images are framed the same way.

So hopefully this demonstration provides a glimpse into how framing, like subject matter, is certainly an important decision, but isn’t the be-all-end-all decision that a lot of people seem to think it is.

In fact, it isn’t even the be-all-end-all decision when it comes to just your composition.

Because it turns out that your technical decisions have as much impact on your “composition” as your framing decisions…..maybe even more.

Which is pretty revelatory, considering most tutorials on composition omit any discussion of technique at all, and instead choose to focus exclusively on your framing decisions (things like rule of thirds, balance, etc.).

And we believe that’s a mistake.

We need our students to see that the aesthetics of an image are not independent from the physics of the image.

Too many people still believe that there’s the ‘technical’ side of photography, and then there’s the ‘creative’ side of photography (they often think of the creative part as ‘having an eye’), and they discuss them as if they are entirely unrelated concepts.

But the two are much more integrated than most people realize. And in many cases they’re the same issue.

Thus, when we talk about developing photographic “vision” at ASOP, we’re talking about the ability to look through the lens and see each of these wildly different possibilities….to see what we know can be done to an image, and not just what our literal, anatomical vision sees.

And that’s the kind of vision we develop in our students.

So to summarize and combine these first two premises: if the most common approach to photography is to put most of your effort into looking for the “right subject,” and then to put your remaining effort into how you should frame or “compose” the shot, we demonstrate very early in our program that this isn’t the best mindset for mastering this medium.

We then further demonstrate that developing an ability to “re-structure” your shot can not only allow you to control what you communicate about your subject (or what people perceive about your subject)….but it can also grant you a more fluent ability to change the aesthetic value of your shot.

Which means the most important skill a photographer can develop is the ability to re-structure an image — quickly, willfully, and on command — whether they’re concerned with narrative OR aesthetics.

Assumption #3

Learning the ‘technical’ side of photography means learning your camera functions, your operating system, and your post-processing software.

[Note: We apologize for the length of this section, but we believe this to be the most important of the 4 premises that we’re addressing on this page]

So how do you go about learning to structure an image?

Well a lot of photographers (including far too many professionals) assume that understanding the technical side of photography basically means knowing your “gear,” or your “tech.” In other words, you first learn the various functions and shooting modes on your camera, and then you learn how to use post-processing software in order to finalize and correct the image.

But we establish very early in our curriculum that putting most of your efforts into learning the camera’s “advanced” features is actually going to limit your capabilities, not expand them.

Wait, how is that possible?

Well, to begin, while a lot of modern camera features appear very sophisticated to the outsider, it’s important to understand that your camera’s operating system isn’t an objective reflection of how photography actually works. Your camera’s operating system is a reflection of the decisions and preferences of the engineers who designed it. It’s a system of programmed responses (a series of algorithms), written by people other than yourself in order to capture images in one way as opposed to another.

And if we established anything at all in the sections above it’s that there isn’t ONE WAY to take a given image. There are dozens, or even hundreds.

But the engineers at Canon/Sony/Nikon can’t predict exactly what you might want to do from one scene to the next, so when they’re writing their algorithms they make a lot of generic, lowest common-denominator assumptions about what you PROBABLY want.

For instance, statistically speaking, people often place their subject in the center of the frame. They also tend to compose the subject so that it is nearer to the camera than other parts of the scene. Etc. So the engineers program the camera’s base-line responses with a lot of these assumptions in mind.

But if your habits stray from those expectations (i.e.: if you want to structure your shot in some of the more unique ways we demonstrated above), then those core program functions will not be sufficient. So the engineers tack on even more algorithms — some “override” functions — that are meant to “correct” the camera’s behavior in very specific circumstances.

And thus, many photographers now look upon this endlessly amended and increasingly complex operating system and assume that their goal is to understand each layer of technology embedded within their camera until they are able to deploy whatever specific “override” function was designed for the exact situation they happen to be in.

Alright, let’s pause.

First, this approach to photography is unnecessarily tedious. This methodology takes months to learn, which is to say that professional photographers typically attend multiple workshops and read countless tutorials until they feel they comfortably understand the entirety of their operating system.

And then next, even once this methodology has been fully digested, it actually confines them to a very limited set of solutions that the engineers at Canon/Sony/Nikon have programmed into their camera.

This is because even the most ‘advanced’ sounding features of your operating system (things like exposure compensation, metering modes, histograms, hdr mode, etc.) are really just a limited set of solutions based on what Canon’s engineers think you should prioritize in your shooting, or how Sony’s engineer’s think you might want to amend their generic programming.

So in short, what we’re trying to establish here is that your camera’s operating system is not “photography” …..it is an engineer’s (or a “product developer’s”) very clumsy and compromised translation of photography.

And you’d be amazed how many professional photographers have learned this medium exclusively through that very limited translation. In fact, many of them don’t seem to know the difference.

Next, and more importantly, these algorithmic functions aren’t just biased and limiting, they’re also very easily confused or neutralized by just about any variable in your scene.

For instance, is there a big difference in light within your scene? I.E: Are there a lot of bright highlights and dark shadows? Well if there are, the algorithms that control your exposure will get confused, and you’ll have to begin chasing a tedious chain reaction of corrective functions on your camera to get the exposure you want.

Are there different layers of space within your shot (ie: something is very near and something else is very far)? Well the algorithms that deal with focus and depth of field will get confused, and you’ll begin chasing a tedious chain reaction of corrective functions on your camera to get what you want.

And now we come to our main point here, which is that, when it comes to STRATEGIZING the image, most photographers have actually been taught to eliminate these variables from their shots altogether. They've been taught that if there are wildly different amounts of light, or wildly different layers of space, or a lot of movement throughout the scene, etc., the camera's algorithms will likely give them unpredictable and inconsistent results.

In other words, because any strong variable in your scene will confront your camera with several choices — and because your camera’s programming can’t possibly read your mind as to WHICH of those choices you want it to make — the primary adaptation that has emerged in recent decades is to teach prospective photographers not to give their cameras any choices to make at all. IE: if you compose a more “one size fits all” kind of shot, your camera won’t have to make so many “guesses,” which greatly increases the chances its algorithms can handle the image.

So that’s what photographers are taught to do.

And it should be noted that this logic is never explicitly stated to photographers; it’s more that these values have just been baked-in to all of photography’s oft-repeated “rules of thumb,” or the ubiquitous “common wisdom” that’s dished out in popular workshops and tutorials.

For instance, if you’ve ever heard someone say, “You should always avoid shooting at noon; it’s better to shoot at dusk” ….or maybe you’ve heard a portrait photographer declare, “you should always take your subject into an evenly-shaded area”……..well, they’re basically telling you to avoid major variations in light because such variations can confuse your camera’s responses.

The underlying assumption is that if you choose to ignore that advice you’ll be constantly stuck trying to “correct” your camera.

And so the lasting fallout from this paradigm is that, rather than be taught to simply bypass and ignore this programming altogether, what professional photographers are being taught to do instead (and to a COMICALLY absurd degree) is to patch together a complicated tapestry of “common wisdom” and formulaic protocols, all of which are stubbornly anchored to the idea of ACCEPTING the limitations of your camera’s programming, and then finding some irrationally convoluted ways of working around those limitations.

Or in short: Photographers have been fed the idea that serious expertise is knowing which bells and whistles on your camera can be used to fight with - or override - your camera’s default programming….and thus, the simpler you make your scene, the less you’ll have to fight with your camera.

Or one final way you could describe this whole crazy mess is to state that most photographers are now learning their “expertise” in two big steps:

Step 1: Spend a few months learning your “tech” — all of the ‘advanced,’ smart-sounding features of your operating system that can be used to override your camera’s default responses…and then,

Step 2: Because those functions are so easily confused by any variation in your scene, you strategically learn to avoid those variations altogether. Rather than ELEVATE your knowledge to where you can handle a more complex scene, you learn to “dumb the scene down” to match the very limited capabilities of the camera’s algorithms. Specifically, you learn a lot of generic, fail-safe formulas that are guaranteed not to confuse your camera’s programming.

Ok, so if this is the way a lot of pros are learning the TECHNICAL aspects of the medium, what impact does this have on their CREATIVE thinking?

Well, if you look at a lot of the more repetitive professional work that’s out there, you can see this mindset on display, because once professional photographers go “all-in” on this algorithms-based approach, they’re all sort of stuck shooting the same generic images. In fact many of them have near-identical portfolios.

For instance, every family photographer has the shot of the family sitting in a field of bluebonnets. Every food photographer has the overhead shot of the plate. Every senior portrait photographer has the shot of a teen in front of a brick wall. Etc. Etc.

And there’s a very logical reason these shots came to prominence. It’s because these are all fail-safe formulas that pair well with the limited capabilities of their cameras’ programming, which in turn allows professional photographers to bypass having to understand anything at all about the underlying properties of the medium, as they can just learn their camera technology instead.

And this, in turn, limits their so-called “photographic education” to mostly just memorizing some markers and reference points that have been engineered into their camera’s interface.

Or to be as blunt about all of this as possible: when it comes to their creative development, professional photographers have been taught to adapt their “eye” toward shooting the very limited set of shots their technology was designed to handle………..as opposed to maintaining their own unique vision, and then learning how to adapt their shooting process to fit that unique vision.

And this is a massive problem in the world of professional photography.

And it’s an even bigger problem in the world of “elite” photography instruction. Which is to say that if you were to enroll in any kind of high-priced photography workshop — like a 4-day intensive experience that might run you anywhere from $4,500 - $6,500 — it’s been our universal experience that your instructor will adhere to this paradigm.

But having said all that, please don’t misunderstand us here. There is nothing inherently wrong with any of those images we linked to above, which is to say that if a student really prefers to shoot that way, by all means, we will make sure they know how to shoot that way.

It’s just that it equally needs to be acknowledged that the reason those images have become so ubiquitous is not because those are the most creative or most complex images that the medium allows for. No, the reason those images became ubiquitous is because they are all relatively simplistic formulas that can easily be learned in a one-off workshop, and all without having to learn anything substantial about the actual underlying science of photography.

And even then, we wouldn’t have a problem with any of that if these formulas were being presented to students as an easy and reliable ‘fall back’ option, maybe for when circumstances don’t allow for a more complex, or more sophisticated image.

But they aren’t.

These images are presented to prospective photographers as “the industry standard.”

And so countless photographers have become trapped within this methodology, having memorized formulas that keep them dependent on their camera’s interface, and making them far less capable of innovating or adapting.

*An aside: if you’re wondering how the majority of the professional community could be taken in by this approach, one of the most significant reasons is that this approach has the unfortunate “veneer of technical legitimacy.” Which is to say that a lot of the terms and features that have been built into your camera’s operating system just sort of SOUND sophisticated to the newcomer.

So when emerging photographers attend workshops that center around using camera technology (like “combining your exposure lock tool with auto-bracketing” or “using your exposure compensation tool to ensure your image doesn’t clip the edge of your histogram”), it satisfies their desire to learn what seems like an advanced and esoteric set of skills.

And while those skills may indeed be esoteric, they most certainly aren’t “advanced.”

In fact, it’s pretty easy to demonstrate that photographers who use those techniques are getting boxed into a very narrow framework, and one that severely limits what they can do with an image.

So as a result of this, we now encounter tons of professional photographers applying to teach at our school - each claiming to be a bonafide expert in photography - but it takes only a few minutes of conversation to discover that they’ve learned to regurgitate the “jargon” that Canon/Nikon/Sony’s engineers have given to them, and they’ve learned how to configure and engage the proprietary solutions that Canon/Nikon/Sony’s engineers have given to them….. but they understand very little about the underlying principles of photography that those engineers were trying to address.

However, the most obvious and most predictable reason this has come to pass is that it’s simply more profitable for the camera companies to promote these methods, because encouraging photographers to be dependent on their own unique set of proprietary solutions is far, FAR more lucrative than encouraging photographers to shoot manually and independently of their own patented technologies.

In fact, if all photographers did shoot manually — via their own independent understanding of photography — there really wouldn’t be much incentive to prefer one brand over another, because most cameras share the same basic internal mechanics.

What varies from camera to camera is mostly just the operating system (the internal software, as well as all of the unique terms and icons) that was designed to govern those mechanics.

Thus, Nikon/Canon/Sony's profitability doesn't depend so much on their making the best camera (physically speaking), their profitability depends on adding new "features" to their operating system that will DIFFERENTIATE their cameras from their competition, and more importantly, features that will abstract the process of photography into a framework that they can have more exclusive control over.

The idea is that if photographers spend several years building their methodology around one unique operating system (one unique set of features, terms, and icons), then those photographers are far less likely to want to switch brands, because doing so would mean having to learn an entirely new system, an entirely new vocabulary, and an entirely different muscle memory.

This is why camera companies have put great amounts of effort into intentionally engineering a lot of unnecessary differences into our cameras. In fact, nearly every “advancement” these companies have made over the past few decades has been far more about establishing their own “brand identity,” as opposed to developing any new mechanisms that might actually improve your photography.

And so now after decades of promotional workshops, and the proliferation of finely tuned marketing jargon, and numerous consumer review platforms validating and perpetuating that marketing jargon, and just the plain old way these camera companies have designed our interfaces…. this comically inefficient, algorithms-based approach seems to have taken hold.

Professional photographers now whole-heartedly believe that the key to their success, their expertise, and their legitimacy, is to master the proprietary technologies marketed to them by Canon/Sony/Nikon/Adobe.

But be warned, this methodology will actually limit a photographer far more than it will enable them, and those who follow this approach are doomed to remain well below the capabilities of the most elite class of professional photographers, and, quite honestly, most can’t even replicate the complexity of the images being shot by our own Photo1 students.

Alright, so what’s the alternative? How can you elevate your abilities to the complexities of the scene, as opposed to avoiding complexity in order to appease your algorithms?

Well let’s start with the fact that if you’re shooting with manual functions (as opposed to programmed functions), you won’t be limited by the painfully intrusive and paternalistic response systems of a modern camera.

In other words, you won’t have to constantly fight with your camera.

And thus you can begin engaging the complexities and variables of your scene very directly, and not through an indirect translation, or a biased abstraction, that was engineered by Sony or Canon.

And as it turns out, this method is actually a lot simpler, a lot more efficient, and requires far less post-processing. Additionally, it frees you from dependency on one specific brand, and allows you to practice photography with any camera you want.

But we certainly aren’t the only ones in the world who advocate shooting manually, so that doesn’t necessarily make our program unique.

Where we differ is in the way that we emphasize to our students that once you do start shooting manually - once you are totally free from having to fight with and constantly override your camera’s responses - you can begin to see the variables in your scene as ASSETS, not obstacles.

In other words, we want to make it clear that we aren’t teaching our students to take the same pictures everyone else is taking, but using manual functions instead of programmed functions (perhaps out of some kind of ”purist” mentality).

No, we want our students to see that the primary benefit to shooting manually is that it frees you up to take entirely different, and more complex kinds of images.

The kinds of images your algorithms can’t handle.

But let’s back up a step. What did we mean when we mentioned seeing the variables in your scene as “assets?”

Well imagine that each variable in your scene provides you with a choice, a choice to make one decision as OPPOSED to another.

So to start with an easy example, if you have a difference in LIGHT within the scene, you can make different decisions about how you want to expose that light. You can expose that light one way, as opposed to another.

Here’s a very rudimentary illustration of that what that choice might look like:

This gives you options (ie: there isn’t only one way to take the image).

Whereas if you avoid variations in light, then you have no such choices to make (and keep in mind that most photographers have been taught to look for a scene in which “one exposure fits all”).

But then, once you get comfortable manually controlling LIGHT (which is easy to do, it really only takes a few weeks), you stop seeing contrasted light as something that will confuse your program functions, or as some nuisance that will complicate your life, and you begin to see these dynamics as assets. At which point you start purposefully hunting for these kinds of light differentials, because you know they can be used to alter the emphasis of the image, or the sensibility of the image.

So with this in mind, let’s take a look at some more ASOP student work. The students who shot these have all become very acclimated to seeking out and USING the light differentials within their scenes:

They don’t have to worry that the light will confuse their algorithms, because they aren’t using any algorithms. Controlling light manually has become very comfortable for them (and we can’t stress this enough, very few of our students identify as being especially “technical minded”).

Next, if there are radically different layers of SPACE within your shot, it again allows you to make one decision as opposed to another, as we see here:

So again, you have choices.

Whereas if you don’t align these kinds of layers of space within your shot, you have no such choices.

And again, once you become acclimated to seeing this kind of spatial disparity as an asset, you can start using your lens to alter the emphasis of the image, or the perceived spatial relationships within the frame.

Here are some ASOP students doing exactly that:

And here’s one more variable: if you have movement within your scene, it allows you to render that movement in one way as opposed to another:

And yet again, once you become acclimated to doing this, it allows you to make alterations to the image based on the passage of TIME.

So once more, here are some ASOP student examples:

So these have all been examples of exploiting photographic variables.

And we need our students to see these variables as “assets.” They are what ALLOW you to generate these effects within your image. These variables should not be seen as ‘obstacles’ that need to be eliminated, simply because they interfere with your camera’s pre-programmed responses.

In fact, if your scene doesn’t have any of these variables, then you very factually can’t make any of these alterations……no matter how awesome and expensive your gear is, which, frankly, seems to be the primary disconnect for people trying to learn photography through their “gear.”

We regularly observe serious photographers, holding upwards of $5,000 worth of equipment in their hands, who are still misaligning and neglecting every one of these principles, and then they can’t understand why their images aren’t coming out the way they wanted. Basically, they got the vague idea in their heads that ”better gear“ will somehow make “better pictures,“ and that perhaps these kinds of effects can simply be achieved by pushing the right button or using the right “feature” on their cameras….and Canon/Sony/Nikon’s marketing teams were all too happy to lean into that assumption.

But the thing is, that’s not how photography works at all. Not even a little bit.

Better gear can rarely improve your photography. True photographic expertise is knowing how to align these variables within your shot so that it enables you to execute these maneuvers. Photography is maybe…MAYBE…10% about the “camera settings” you use. And even more to the point, if you don’t understand that first part, then “knowing the right camera settings” won’t get you very far.

The dark, un-acknowledged truth within the photography community is that most professional photographers get their results by using a “camera setting” they were taught would produce a particular effect, and then when that camera feature INITIALLY fails…..well, after repeating the shot 7 or 10 or even 15 more times, those photographers finally, eventually, get the result they wanted.

And then they just sort of gloss over why the very last attempt “worked” and all the previous ones didn’t. In fact, they’re even taught to view those initial misfires as a legitimate part of the process — that those misfires are just the inevitable “cost of doing business” — with the implication being, “Eh, photography’s not really an exact science; sometimes you have to repeat a shot a few times to get it to work, god only knows why.”

And worst of all, this method reinforces to them that those “camera settings” did, in fact, eventually get them the result they wanted…..and so they hardly see the need to question their training.

A staggering, STAGGERING amount of professional photography is practiced this way.

But we need our students to see that relying on that kind of “trial and error” methodology puts a very low ceiling on your photography. If you want to be able to reach a higher level of sophistication with your image structures (and achieve a higher aptitude for problem solving), you need to know how to execute each of these maneuvers on the first try, because…..and here’s where this approach really takes off….

Once you understand how to enact any one of these strategies, we can now begin to COMBINE these maneuvers.

Which is what structuring an image is really all about.

There is no limit to how you can combine these decisions, but let’s take a look at one popular combination.

What if we were to combine the lighting sensibility of this picture:

With the spatial emphasis of this picture:

The result would look something like this:

Again, these are all student images. And again, while these results may appear to be very “creative” or “sophisticated” to the layperson, to ASOP students, these methods are just very logical and obvious. It’s simply a matter of first understanding each of these individual properties very throughly, on their own, and then understanding how it is that you can combine them. Which is to say that it’s more about understanding the components of photography than it is about understanding your “tech.”

And while this illustration represents one specific combination, there are near-infinite ways you can combine the elements of photography. And the more of these maneuvers you combine, the more uniquely you can structure your image.

So one of the core themes of our program is that the ability to author an image - the ability to get a shot that is more ‘dialed-in’ to your specific intentions, or your own unique voice - is totally dependent on being able to DIFFERENTIATE your picture from what someone else might have done with the same scene.

But you can’t differentiate your shot if you don’t put any variables in front of your camera that allow you to differentiate your shot.

That may sound obvious, but the bizarre reality we’re living in is that a lot of serious photographers are actually being taught the opposite, they’re being advised to avoid these assets - to rid their shots of these variables altogether - in order that they can continue to use all those smart-sounding features they learned about in their workshops…which is maybe the single biggest reason we founded ASOP.

[SIDE NOTE for any educated photographers who might be reading this: one of the most common arguments we hear professionals make in defense of their algorithms-based approach is that they actually can get certain SINGULAR results using their algorithmic technologies, just by repeating the shot several times. In other words, maybe they don’t get the result they want on the very first try, but perhaps on the fourth, fifth or sixth try, if they just fight with their camera a little bit, and ‘bracket’ the shot (for those who don’t know, “bracketing” basically means shooting several “takes” in order to hedge your bets). These photographers are adamant that it’s much easier to “mess around with your settings for a few shots” than it is to spend several months learning the more substantial, underlying properties of photography. But the problem with this methodology - aside from its gross unreliability and inefficiency - is that it very factually limits photographers to using just “one trick” at a time, because this method completely breaks down once a photographer needs to COMBINE these variables into a more complex image structure. ….In other words, if a photographer needs to manipulate 3 or 4 of these dynamics within the same photograph, they absolutely have to know how to get all 4 results on the very first try, because it would take thousands of attempts to achieve a randomly miraculous alignment of 4 different photographic principles through bracketing. But yes….it is true that you can often get one single dynamic to come out by way bracketing (basically through “trial and error“) which is unfortunately what a lot of photographers are doing right now. And it’s the biggest reason so many professionals shoot what we refer to as ”one-dimensional” images. “One-dimensional” means that they’ve manipulated one single aspect of the image…but that’s all. For instance, maybe they’ve used their aperture to blur the background…but that’s all. Or maybe they’ve “panned” a moving subject…but that’s all. In fact, most professional portfolios are littered with images that use exactly one “trick” at a time, because when you use what is essentially a “trial and error” methodology, that’s the absolute ceiling of what you’re capable of achieving. So it’s worth repeating: there are very defined limitations placed on any professional photographer who embraces their camera’s algorithms. Or to be as clear as humanly possible: the fact that the current “industry standard” for professional photography is to use exactly one “trick” at a time serves as a strong indication that most pro photographers have just been taught a lot of “trial-and-error” methodology……and then that flimsy methodology gets dressed up in just enough industry jargon to make their methods SOUND legitimate to the public. And this is precisely the reason we hate photographic “jargon” so much at ASOP. It isn’t just that it’s a silly, elitist, and exclusionary language (although it is), it’s more the fact that ‘photo jargon’ obscures the fact that an awful lot of modern photographic strategy is hollow and superficial, and it obscures that fact not only to the general public… but even to the very photographers who use and perpetuate that jargon.]

Finally, go ahead and take a look at some of the more polished work our students do when exiting the program and note how many of these variables they’re exploiting:

As a side note, it might also come as a surprise to know how little post-processing went into these images. Hardly any at all. The ones that have a bit of an ‘artificial look’ were actually achieved in-camera, but with the use of studio lighting equipment.

So one added benefit to this methodology is that you don’t have to spend nearly as much time in post-production “fixing” your algorithm’s inadequacies, or trying to spice up a bland image your camera “features” stuck you with.

We encounter a lot of professionals who honestly believe that post-processing is actually where most of the hard work is done. They say things like “a photo shoot is 30 minutes of shooting, and then 4-6 hours of post-processing,” which is INSANE. That almost never needs to be the case. If you truly understand photography, and not just Canon/Sony/Adobe’s proprietary technology, it takes only a few minutes to achieve an entire batch of results like this, in-camera, whereas it takes hours to dramatize a sizable batch of images using post-production.

But most professional photographers are currently wasting 20+ hours a week in post-processing, or hiring an assistant to do it for them, because they honestly believe that’s just how photography works. Because that’s what their workshops and tutorials have taught them.

So overall we hope this demonstration provides a small glimpse into the kind of progression our students undergo. Our students first learn all of the ways these variables can be exploited individually…..and then they learn how to combine those maneuvers into more sophisticated and more unique constructs.

So getting back to our earlier premises: if it can be said that the single most popular approach to photography in our culture is to look for a “good subject” and then to think mostly about how you want to compose that subject (ie: the classic “amateur approach”)….. well then the second most common approach to photography in our culture is to hunker down and learn your gear and your “tech” (ie: learn Sony/Canon/Adobe’s limited and biased proprietary solutions). And you can think of this last approach as the “professional approach.”

Our curriculum demonstrates, very thoroughly, that both of these roads lead to dead ends, just in opposite directions.

And as an added note, the next time you stumble upon a photographer whose images seem more dynamic and more engaging, but you just can’t quite put your finger on why, we’d ask you to consider that it isn’t that those photographers are mystically or inexplicably more “talented” …..it’s that they’re embracing the properties of photography rather than avoiding them.

And once you see this distinction between photographers who use the variables in their scenes, and the photographers who avoid them, you can’t unsee it.

Which leads us to our fourth and final premise….

Assumption #4

Photographic abilities are based largely on talent. Some people have an “eye” for this, and some don't.

Throughout the past decade, we’ve had the opportunity to test this notion to exhaustion, and we’ve concluded that there is no talent quotient in photography.

And as the specific author of this piece, if I may speak from personal experience for a moment, this is a premise I bought into myself when first starting out. I was accepted into a major college program, one that admitted only 8 new students per semester, and it was made very clear to us that we had been selected by our elders to be the next generation’s ‘seers’ and narrators.

In fact, the entirety of the art school process is predicated on the idea that students accepted into major art programs are an elite few. They are told that they possess “an eye” for this, an eye that not just anyone has, and thus the art department's job is not so much to teach them anything substantial about how photography works, rather the art department’s job is to nurture and guide the natural talent they already had upon entering the program.

And looking back, it’s not surprising that so many of us bought into this, because, to a 19-year-old art student, this idea is marvelously self-serving. We were the special visionaries, we thought….uniquely equipped to handle the important task of cultural narration.

And this mindset heavily influenced the earliest versions of our curriculum at ASOP. We, too, concluded that the students who were getting the best results were simply the students who had a strong “knack” for this.

But here’s the thing. While the notion of a “photographic eye” may seem romantic, it just isn’t true.

It turns out, as soon as everyday, ordinary citizens are exposed to a lot of very specific, very constructive insights about how photography works….suddenly, everyone has “an eye.”

This is far more about visual literacy than it is about having a unique or mystical ability.

What our culture misidentifies as photographic ‘talent’ is the far less romantic idea that some people are simply outliers in how their natural, unconscious habits are likelier to lead to more successful images.

In other words, if you take a large enough sample of people - say, 100 people - there will be a vast disparity of habits and preferences that lead all of them to behave slightly differently with a camera in their hands. And in that group of 100, maybe 10 of them have habits and inclinations that - through random chance - happen to overlap in some really beneficial ways, which means they produce a higher output of images that are perceived as “successful” or coherent.

Our society then takes that small pool of outliers and labels them as “talented.”

We say they have an “eye” for this, or a knack for this.

And because most photographers experience these initial successes (or failures) as a result of totally unconscious habits, it means that in the same way that “untalented” photographers don’t know what they’re doing wrong, “talented” photographers often don’t know what they’re doing right.

This phenomenon is reflected in the tendency for very successful photographers to have a hard time articulating exactly what it is they do. In fact, it is very common for notable photographers - during “artist talks” or symposiums - to dismiss their methodology as being indescribably intuitive or instinctive. When asked about their methods, or why they made particular choices within a given photograph, they often can’t quite put their finger on exactly what they did.

And then a very common outlet for them is to make a self-deprecating joke about how they don’t really know what they’re doing, they just get lucky a lot!! (which usually gets a relieved laugh from the audience).

But to our observations, those photographers aren’t being dishonest, or even humble. It’s just that their natural habits and tendencies made them statistical outliers in terms of the results they were getting. And because their teachers simply dismissed their habits as “talent,” they were never really forced to examine what precise factors were leading them toward getting more effective images.

In other words, like a lot of photographers, they practice this medium unconsciously.

And it’s that unconsciousness that seems to ensure that photography is perpetually stuck in its very first stage of evolutionary development.

Because just as early humans initiated our verbal language with a lot of unconscious grunts, modern day photographers still seem to want to unconsciously and instinctively point their cameras at “things they find interesting.”

And then our society rewards the ones who inexplicably “happen” to get good results.

But like our verbal language - and like our written language - photography is a lot more learnable than our culture lets on. If we’ve proven nothing else with ASOP’s curriculum, it’s that photography is not a mystically in-born talent.

Anyone can do this.

But in order for that to be the case, this medium can’t be practiced unconsciously, by the random few who’ve lucked their way into some useful habits. No, in order for the average person to be able to produce results that are as vivid and riveting as those “notable” photographers, this medium needs to be practiced very consciously, and very purposefully.

In fact, it’s no small problem that our culture often chalks this up to “talent.”

For one thing, it’s very exclusive of, and discouraging to, the majority of people who don’t identify as being creative or talented.

Many people conclude, very early in life, that they don’t have a natural “eye” for this, and then once they’ve branded themselves as “untalented” they don’t even attempt to pursue photography on a higher level, meaning they make no serious attempt to become photo-literate at all.

Which is a massive societal problem, given how many people are being condemned to a lifetime of photo-illiteracy in a society that increasingly uses this medium as a form of commercial and ideological communication.

Imagine being discouraged from learning to read and write, simply because the very first time you tried to write a sentence as a child it didn’t happen to come across as particularly coherent, leading to you then being branded as “untalented” at reading and writing, and therefore unworthy of admission into any school that specializes in reading and writing.

That’s more or less what our culture is doing with photography.

But we at ASOP have repeatedly observed that once you illustrate, in a relatable way, the exact factors that lead to more effective and more coherent images, it’s pretty easy to get people to understand and control those factors.

And then voila, their images gradually start looking indistinguishable from the images shot by “talented” photographers, not because they’re mimicking, mind you, but because they’ve consciously adjusted their habits in order to very willfully get whatever result they want when they’re shooting.

And we find that this pretty much levels the playing field entirely. We’re not kidding. Students who enter our program nervously confessing about their lack of creativity, or joking that “they barely know how to turn their camera on,” have had no observable disadvantage compared to students who identified as being “creative,” or even students who’d already had some professional photography experience before taking one of our classes. Neither factor has shown to have any correlation to the abilities our students can demonstrate upon exiting our program.

The truth is, many of our students come to us simply because they have an upcoming vacation they want to capture, or because they’ve recently had a child, or because they were given an expensive camera as a gift. And then we suck them into our vortex. And 8 months later, they’re often outperforming most seasoned professionals.

And this has lead us to the position that there isn’t really any in-born talent quotient in photography. Photography is less like being able to throw a 95 mile-an-hour fastball, or having been born with a perfect singing voice, and is more like speaking a language.

And while some people are certainly more articulate speakers than others, in general, the vast majority of people in this world are quite capable of speaking effectively within their own language. Because for all the jokes our society likes to make at the expense of the “average person,” the truth is, when it comes to speaking, the “average person” routinely demonstrates an ability to express very complex tones-of-voice such as humor or sarcasm, or to lower their voice when they need to sound consoling, or to raise their voice when they need to express anger, etc… often within just one conversation.

All things considered, people are tremendously articulate.

And again, while some people may be ‘better’ speakers than others, we don’t generally say that you need “talent” to be able to speak. You just need to be literate or fluent.

And that’s a rough analogy to what we’ve found to be the case with photography. You don’t need talent, you need literacy.

ASOP’s purpose is to give people that literacy.

It was not so very long ago that the statistical majority of our population could neither read nor write. In fact, throughout certain stages of civilization it was just assumed that some segments of our population didn’t especially need to be literate. And if that notion sounds comically outdated to our modern values, just consider how off-putting this current generation will seem to those that come, given how many of our most famous photographers, and even our college professors[!!], continue to perpetuate the notion that you have to have a special talent, or that you have to be a special ‘seer,’ in order to do this.

Anyone can do this.

Final Summary

When people first consider learning photography, they tend to have a lot of misguided notions about the process. And understandably so.

They ask things like, “can you teach me how to shoot food photography?” Or, “can you teach me how to use my Nikon d3400?”

But these questions are a bit like asking a language instructor, “can you teach me some sentences with the word ‘food’ in them?” Or asking a creative writing instructor, “can you teach me how to structure the plot of the novel I’m working on and how to develop my characters….but specifically on Microsoft Word as opposed to Apple Pages? How does Microsoft Word help develop characters better than Apple Pages?”

And the unfortunate truth is that most workshops and tutorials are all too happy to lean into these misconceptions, profiting from the most simplistic assumptions made by the common layperson.

But at ASOP, we don’t believe the best way to learn photography is to start with a particular subject matter and then to reverse-engineer one specific formula for shooting it.

Nor do we believe the best path is to learn one profit-driven company’s proprietary software as opposed to another profit-driven company’s proprietary software (Sony vs Canon, for instance).

And we certainly don’t believe that our job is to nurture the pre-existing talents of a hand-picked, like-minded group of students.

We’ve witnessed, first hand, how each and every one of those approaches leads to dead ends (or at least leads to extremely limited results), which largely explains why so many people in our culture can attend multiple photography classes and still might not see any substantial improvement in their shooting. Students exit those educational experiences either believing that they aren’t talented enough, or that they haven’t bought the right equipment. And in turn, this lets those photography schools off the hook.

And this is why we’ve founded ASOP.

The most effective way to learn photography is to first build a solid understanding of all of the universal properties of the medium that will allow you to re-structure an image - in dozens of different ways - regardless of what brand of camera you own.

Next, you then need to learn all of the ways that those properties can be combined so as to configure an image to fit different kinds of styles or purposes.

After you’ve learned that, you can look for any subject you want, and when you find it, you’ll know dozens of ways to articulate that subject, and you’ll know how to do it using any camera you can get your hands on.

ASOP’s goal is to provide people with that ability.

Thanks for reading,

- Andrew Jacob Shapiro

Founder, Austin School of Photography